The Carl Brashear Story

"Men of

Honor"

Written by Madalyn Russell for

Underwater Magazine.

If it is difficulty that shows what men are, there should be

no doubt about what kind of man Carl Brashear is. The Navy's first

African-American Master Diver, Brashear faced difficulties that would have

defeated most people. His spirit and determination resulted not only in his

overcoming great odds to become a U.S. Navy diver in the first place, but also

in his surviving the loss of a leg in an accident on the USS Hoist in 1966 - and

more amazingly - in his attaining the rank of Master Diver after that accident.

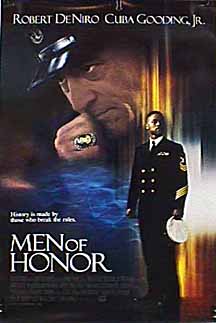

In the fall, Twentieth Century Fox will release Men Of Honor, the story of Brashear's struggle. Cuba Gooding Jr. stars as Brashear. The film also stars Robert DeNiro as Billy Sunday, a senior officer and Master Diver who is at first another obstacle, but who ultimately helps Brashear overcome his crippling injury, as well as racism and bureaucracy, to make military history.

Brashear joined the Navy in 1948 at the age of 17. The film follows his acceptance into dive school, his training in the Mark V gear, and the accident that could have ended his career. Brashear's struggle to convince the Naval Bureau of Medicine and Surgery to allow him to continue diving is an integral part of the story.

No Hint of Things to Come

Carl Brashear was born in rural Kentucky in 1931. His family moved to Sonora,

Ky., when he was only two weeks old. He grew up swimming in creeks and rivers

near his home, but there was nothing to indicate that his life would take the

twists and turns that eventually resulted in his spending almost 32 years in the

U.S. Navy, becoming not only the Navy's first African-American Master Diver, but

also its first amputee diver.

Brashear joined the Navy as a steward. He was sent to a Beachmaster's unit in Florida, and there he first saw divers in Mark V gear. He was hooked. In 1949 he qualified using the Jack Browne rig, then progressed to the Mark V in 1953.

Gaining official diver status was in itself quite an achievement at the time. Brashear attained the rank of Chief Petty Officer E7 and worked successfully, but relatively uneventfully, until March 26, 1966, when the determination that he had originally called upon to help him become a Navy diver would seem almost feeble in comparison to the tenacity that he would need in order to stay a Navy diver.

One Mishap Leads to Another

On January 17, 1966, a U.S. Air Force B-52G bomber carrying a hydrogen bomb

collided with a KC-135 refueling tanker off the coast of Palomares, Spain. In

March, aboard the USS Hoist, Brashear and his crew were taking part in efforts

to retrieve the nuclear weapon in 2,500 feet (758m) of water.

Brashear had rigged a three-legged "spider" with grappling hooks on each leg. It was attached to the submersible Alvin, which would use it to attach parachute rigging to the bomb. The apparatus worked beautifully and the bomb was brought to the surface.

At 5:00 p.m., a shift in the position of the ship that had pulled alongside the Hoist to receive the bomb caused a chain of events that almost killed Carl Brashear and seemed certainly to have killed his career in the Navy. During efforts to bring the bomb aboard, a swell caused an unexpected movement in the ship's position. The timing was catastrophic. The atomic weapon slipped from the parachute rigging and sank again, but even worse, a pipe broke loose from one of the ships and became a deadly missile.

Brashear saw the pipe break. "I got all my sailors out of the way, but I didn't get myself out of the way," he says.

The injuries he suffered were overwhelming, and so sudden that at first, he didn't know anything was wrong. Only when he tried to put weight on his leg did he realize the extent of the damage. He jokes about it today. "I found that I didn't have a leg to stand on," he chuckles.

Most of the flesh on his leg was ripped away, leaving his foot attached only by the tendons in the back of his calf. Bones were exposed and the bleeding was profuse. He also suffered head and internal injuries.

The dive boat did not carry a doctor. The corpsman did what he could, but his attempts to stop the bleeding were useless. He finally resorted to the use of two tourniquets - not accepted practice, but the accepted pressure-point method was not working. Brashear credits the corpsman, whose name he does not know, with saving his life that day.

The nearest doctor was on the USS Albany, six miles away. When the Hoist rendezvoused with the Albany, the physician on board called for Brashear to be airlifted by helicopter to a hospital in Spain. He was loaded aboard, but events took another bad turn when the aircraft proved to be too low on fuel to make it to the medical facility. It landed on a dilapidated runway and waited until a small plane arrived to finish the trip with Brashear, who was miraculously still alive, but near death. As he describes it, "The helicopter ran out of gas, and I ran out of blood."

When Brashear finally arrived at the hospital six hours after the accident, he was declared D.O.A. The examining physician ordered that he be sent to the morgue, then decided to check one more time for a heartbeat; he detected a very faint one. "I survived the morgue," Brashear laughs.

The bleeding continued in the hospital, but after transfusions totaling 18 pints - almost twice the volume of blood ordinarily found in an adult human body - Brashear regained consciousness.

Doctors tried bone and skin grafts to save his leg. Gangrene later set in. Brashear was sent to Weisbaden, Germany, and then to Portsmouth Naval Hospital in Virginia. Efforts continued to the point that, in May, after almost two months of frustrating failures and setbacks, Brashear had had enough and requested that the leg be amputated.

In four "guillotine" surgeries - removal of layers of the limb until all infection is gone - surgeons removed Carl Brashear's leg, finally stopping four inches below the knee.

Never Give Up

Most people would have given up hope of remaining in military service at that

point. Not Carl Brashear.

Still attached to the Naval Hospital, he was fitted with a permanent prosthetic limb in November of 1966. In December, he sneaked out of the hospital and managed to dive in a deep sea rig, taking pictures that would help him make the case for continuing his diving career. (The Navy had already begun the process of having him discharged because of his disability.)

Although the doctors saw photographic proof of his continued ability to function as a diver, they were "in total disbelief," says Brashear. They were still not convinced that he could do the job. He kept sneaking out, arming himself with more photos, until he finally prevailed.

When the doctors relented and he was ordered to the Deep Sea Diving School in Washington, D.C., Brashear had to prove himself by completing tests that were much more demanding than any he had previously encountered as an aspiring diver.

Wearing the 190-pound Mark V, he demonstrated his ability to climb ladders and to dive. On the surface, he had to walk at least 12 steps, wearing the Mark V helium/oxygen rig - all 290 pounds of it. He was also required to dive in scuba gear and engage in physical training with other dive school students. That physical training included calisthenics and running.

When Brashear ran, scar tissue would break loose and blood would leak into his artificial leg. To prevent infection, he would remove the prosthesis and soak what remained of his leg in warm water laced with hydrogen peroxide or Betadine. He never told his doctors about the problem because, "I hadn't made Master Diver yet." That goal kept him going.

In March of 1967, doctors finally okayed his transfer to Second Class Diving School in Norfolk, Va., and in April 1968, he was restored to full active duty and full diving status - the Navy's first amputee diver.

Is There Life After Diving?

Carl Brashear retired from the Navy in 1979. That same year, NBC filmed a series

called Comeback, which highlighted his successful return to diving, as

well as the comebacks of John Wayne, Rosemary Clooney, Neil Sedaka, and Freddie

Fender. Pretty heady company.

In 1980 a deal was under consideration to produce a movie about his exploits, but it fell through. Today he laughs about that failure. "God wasn't ready for it to happen," he says. "Cuba Gooding wasn't around then."

Brashear is rightly proud of his record and the tenacity he displayed. "I have never been on limited duty," he says, "not one day, not one hour."

After retirement from the Navy, he was still not one to sit back and relax. He attended college in Maryland and studied environmental science, then worked for the government, first as an Engineering Technician (GS5), and later as an Environmental Protection Specialist (GS11). He retired from that position in 1993. The father of three adult sons, he now lives in Virginia.

Divers Institute of Technology Goes Hollywood

Divers Institute of Technology (DIT) still teaches Mark V diving and, according

to its Director, Cmdr. Bruce Banks USN (Ret), is the only school that trains in

real open water conditions for deep dives to 165 feet (50m) on air, and up to

200 feet (61m) on mixed gas. Twentieth Century Fox commissioned the school to

assist with the filming of Men Of Honor. Cast members, including DeNiro

and Gooding, went to the school's facilities in Seattle, Wash., where Banks,

along with Master Divers Richard Radecki, USN (Ret), and John Searcy, USN (Ret),

provided training in U.S. Navy diving history, physics, medicine, and Mark V

dress. The actors also completed indoctrination dives in Mark V and Superlite 17

rigs.

In June 1999, Cuba Gooding Jr., Director George Tillman Jr., and nine others from the film's cast arrived at DIT and began some pretty rigorous, though abbreviated, training to introduce them to the world of diving. The indoctrination began with a quick half-mile run led by ex-Marine Sergeant Steve Mollison. Apparently Mollison made a favorable impression, because he went on to appear in several scenes in the film, traveling with the cast to Rainier and Portland, Ore., as well as San Pedro, Calif.

After physical training, the next step was the shortened course in diving physics, medicine, and the effects of air embolisms and decompression sickness. The Hollywood contingent was a hardy bunch. Undeterred by the thought of embolisms and bends, they progressed to setting up dive stations using U.S. Navy Mark V diving rigs and dressing out in the gear for an indoctrination dive.

Gooding made his indoctrination dive in the Superlite-17. After observing his diving performance, DIT's Banks commented, "Cuba took to the water like a professional."

While the actors were undergoing dive training, prop director Will Blank and set director Kate Sullivan were selecting artifacts for use on the set. They chose more than 200 items for use in the film. DIT provided diving equipment for 15 dive stations, including helmets, an underwater telephone, canvas suits, Mark V umbilicals, deep sea knives, hand air pumps, cutlery equipment, etc.

In early August, Robert DeNiro began his diving introduction training at DIT. In a program similar to the one provided to Gooding and his group, DeNiro received instruction in physics and medicine, but he was also schooled in the duties of a Master Diver within a U.S. Navy Dive Team. He observed Master Diver Radecki in charge of a deep diving class and performing surface decompression dives off the DIT dive boat M/V Response. DeNiro watched as Radecki ran a dive with stopwatches, directing students in surface intervals and decompression using oxygen in the double lock chamber located aboard the Response. He also learned about the leadership skills and the demanding selection process that the Navy uses to select its Master Divers. DeNiro not only watched everything carefully, but he also videotaped every aspect of his experience at DIT for later study.

Lights, Cameras, Dive!

In addition to the initial training of Gooding, DeNiro, and the others, DIT was

asked to provide technical support throughout the filming of Men Of Honor in

Portland and Rainier, Ore. (depicted in the film as the Navy Dive School in

Bayonne, N.J.), and to provide support aboard a U.S. Navy fleet tug outfitted as

the World War II Salvage Ship Recovery, in San Pedro, Calif. That support

included daily technical direction by Banks and Radecki to the film's director,

George Tillman, and to Gooding and DeNiro. Banks and Radecki gave advice and

instruction regarding the diving operations conducted at the "Bayonne"

school; Navy procedures; protocols on how students at a Navy Dive School are

selected, trained, housed, fed, and how they respond to a strict code of Navy

discipline and procedures. Because of Radecki's Navy background in salvage as

well as diving, his advice proved to be particularly helpful in making the

rigging and diving for the ocean scenes very realistic.

For actual in-water operations using the Mark V dive rigs, the cast of the film shared the stage with a crew of 15 DIT students and recent graduates. The students/graduates were on the set in Rainier, Ore. Banks reports that they "dressed in Mark V gear and dove off the pier of the 'Bayonne' school and supported major scenes in the movie. DIT students also performed many of the actual at-sea stunt diving, using Mark V diving dress, diving stages, and surface dive station set ups." Even Banks himself got into the action, portraying a dead helicopter pilot recovered from the ocean by DeNiro. About his experience on a movie set, he reports, "The 'Hollywood' catering was first class, with lots of lobster, fish, and gourmet food." Another interesting fact relayed by Banks is that many of the pierside scenes were cast with actors in fake Mark V dress, including plastic helmets, weight belts, and shoes - much lighter in weight than the real thing.

Banks has high praise for the acting chemistry between Gooding and DeNiro. He characterizes their interaction as powerful, and reports that the script has "humorous subplots built around ethics and integrity." Banks added, "The movie should spark interest in commercial diving for today's youth." Banks was particularly touched by a surprise that arrived at his office after the filming was over. Inside a carefully wrapped package was a polished cherry box containing a gimbaled Swiss six-inch ship's chronometer set. An inscription read, "Dear Bruce, thank you for your generous support, your wisdom, and experience. You were great. Take care, and thanks, Bob DeNiro."

The Finished Product

Carl Brashear was on the set of Men Of Honor for several days. He was

amused by Gooding's reaction to the Mark V gear worn in his role as Brashear.

Gooding confided that he was a little frightened "when the lights went

out" after the helmet was lowered over his head. Later, he had a brief

moment of uneasiness when water leaked in and the tender had to tighten the

helmet. At that point, if he didn't have it already, Gooding probably developed

a very healthy respect for all divers, and for Brashear in particular.

Brashear is pleased with the finished product. He, too, describes the film as "powerful" and "very close to the real thing." In fact, he confides that some scenes were almost uncomfortably real.

Director Tillman, Gooding, DeNiro, and an impressive cast that includes Charlize Theron, Hal Holbrook, David Keith, Michael Rapaport, and Powers Boothe, have apparently done an outstanding job of bringing this story to the screen. They may receive accolades - maybe even awards - for their work, but below the "glitz and glamour" of a Hollywood film, Men Of Honor is Carl Brashear's story. Without his strength and courage, there would have been no story to film.

It's been said that skill and confidence are an unconquered

army. It can also be said that skill and confidence (and a never-give-up

attitude) are the stuff from which an unconquered Master Diver is hewn.

VISIT THE OFFICIAL MOVIE SITE at www.menofhonor.com

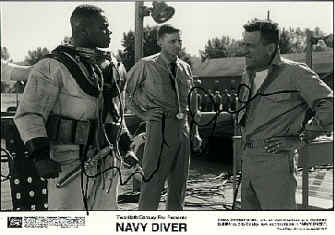

Above is a picture of Carl Brashear's Class from Salvage School in Bayonne, NJ 1954. Carl is on the top row, second

from the right. Joe Fontana is on the bottom row, second from the right.

This is Carl's graduation class. 22 OCT 1954